Join children historical fiction authors Chris Stevenson and Robert Skead as they discuss their books along with teachers who love history.

Click here to sign up for the Zoom meeting

Join children historical fiction authors Chris Stevenson and Robert Skead as they discuss their books along with teachers who love history.

Click here to sign up for the Zoom meeting

George Washington (aka Levi) wants to remind the public of the importance of voting.

Five fun facts about Washington’s own election:

Times have changed, but the importance of voting hasn’t! GO VOTE!

The sequel to The Drum of Destiny will be out in 2018! Simon & Schuster/Liberty Bell Press will be publishing Cannon of Courage which follows Gabriel Cooper’s journey through the American Revolution. In Cannon, Gabriel joins Henry Knox in a daring trek across hundreds of miles of wilderness in the dead of winter to retrieve the one thing that can drive the despised British from Boston, CANNON! Gabriel and Henry Knox attempt to accomplish the impossible, bringing Fort Ticonderoga’s cannon back to Boston. To do so, Gabriel must face untold challenges; bears, Indians, and ice. All while trying to find his way as Washington’s aide-de-camp. CANNON OF COURAGE continues DRUM OF DESTINY’S fight for freedom.

Henry Knox’s journey is an amazing, and often overlooked, piece of American History. The Knox Trail is well-marked with various monuments documenting the path Henry and his brother William took from Fort Ticonderoga to Cambridge. Henry was age twenty-five and his brother William was only nineteen when the two set out to get the cannon from Ticonderoga. Their three hundred mile path navigated multiple crossings of the Hudson River and difficult mountainous terrain. Henry chose to make the journey in winter to allow the use of sleds instead of wagons. Wagons were cumbersome, prone to breaking, and often became mired in mud. Sleds pulled by oxen over snow would provide a much quicker mode of transportation.

The weight of all the cannon towed from Ticonderoga totaled approximately 120,000 pounds. Some of the cannon were 11 feet in length and weigh 5,000 pounds. Henry’s ingenuity and perseverance made the journey a success. Ticonderoga’s cannon made it to Cambridge in what Henry described to Washington as a “noble train of artillery.” The cannon were key to the patriot army driving the British from Boston in March 1776.

I’m looking forward to Gabriel showing young readers this amazing piece of American History and what creativity, hard work, and perseverance can accomplish! Stay tuned for more specifics on the release.

I’ve had the opportunity to speak to a few thousand kids in schools all over Indiana over the past few weeks about history, writing, the American Revolution, and most importantly, my all-time favorite founding father, George Washington. I get to share with these kids what has drawn me to love Washington, and what made him such an incredible leader: The self-sacrifice he was willing to make for others and for a cause bigger than himself. More than ever, kids need to understand what it means to give sacrificially.

As part of my school presentations, I show kids the picture of Washington on the dollar bill, and ask them who it is. Everyone gets it right. Then I show them this picture and ask them to guess who it is. I usually get guesses ranging from John Hancock to King George. Nearly every time, I have to tell the students that this is a painting of George Washington, and that during the Revolution he looked much more like this guy than the old guy on the dollar bill.

1772 portrait of Washington in his Virginia Regiment uniform

Washington was just 43-years-old when he took command of the Continental Army in 1775. He was extremely fit, tall, graceful, athletic, and was reportedly a good dancer. Not only that, but he was extremely wealthy. Washington owned about 7,600 acres of land in Virginia, had a beautiful home at Mount Vernon, and in today’s dollars was worth roughly $580,000,000.00. Kids are always amazed to learn that Washington was relatively young and extremely rich when he decided to leave his home to take command over the rag-tag New England army that had gathered around Boston. I then ask a question most kids have never thought about: What happens to Washington if England wins the war? Usually silence fills the room as kids ponder the reality of what Washington was willing to sacrifice to fight for freedom and liberty. If England wins, George Washington would have been charged with treason against the King, undoubtedly found guilty, and would have been hanged. When Washington accepted command, he had to know that not only would he have to leave behind a life of luxury at Mount Vernon, but he would also be put to death by hanging if the colonists lost the war.

People followed Washington because they all knew how much he was willing to give up for the cause. In his Pulitzer Prize winning book 1776, David McCullough writes:

To be sure, Washington had his faults. He could be indecisive, many times his strategic military plans were misguided, and he lacked formal education. He more than made up for his flaws, by his ability to lead others from his heart. Washington was able to lead so well because he gave something up of himself to do so. He was genuine and vulnerable and his soldiers loved him for it.

Thankfully, we won the war and Washington wasn’t convicted of treason and hanged. He was able to keep an ever changing group of army recruits together over a period of eight years. Then Washington did something that turned the world upside down. He resigned his commission as Commander in Chief of the Army, giving up his power. Over the course of human history nearly every military leader similar to Washington took the power they had gained through military conquest and used it to rise to power as a king or dictator.

John Trumbull’s painting of General Washington resigning his commision

I sometimes ask kids what they would do in that situation. Imagine that they had just spent eight long years away from home leading men into battle, enduring the elements of the weather, being questioned by Congress, and constantly battling a lack of supplies. For me, I tend to think that I would have not resigned, and instead felt like I deserved the power that I had earned. If they’re honest, most kids think the same. However, Washington didn’t keep his power; instead he gave it up.

I tell kids, I want to be like Washington, and I hope they do to. I think some kids get this idea that we can learn important life changing lessons from history. After my talks I’m even hopeful that a few kids grasp the idea that life isn’t just about them. Living by giving yourself up for others is what makes true leaders, just like George Washington.

What event made the American Revolution possible: The Boston Massacre; The Boston Tea Party; the British closure of Boston Harbor? While these events certainly helped solidify patriot resolve against British tyranny, there’s another often overlooked story that led to thousands of Bostonian’s joining forces against British rule. In the winter of 1774, snow-covered the roads and hills of Boston, which made sledding ideal for any thrill seeking boy. Copp’s Hill on Boston’s North End made a perfect sledding spot for a boy with a wooden sled and a desire to go fast down Boston’s streets.

Boston’s North End and Copp’s (Corps Hill)

One such boy was sledding down Copp’s Hill when his sled ran into a man by the name of John Malcom, knocking him to the ground. Malcom was a customs officer and ardent Loyalist. He was also known to lose his temper and was generally disliked, especially by patriots. Malcom began shouting angrily at the boy who had just struck him with his sled. As he was raising his cane to strike the boy, a neighbor named George Hewes came out into the street and ordered Malcom to put down his cane and leave the defenseless boy alone.

George Hewes Portrait (Cole 1835) Hewes lived to the age of 98

George Hewes was a known patriot having participated in the Boston Tea Party just a few months before. Malcom, a former British soldier and now important British official, turned his anger on Hewes who was a simple Boston shoemaker. Malcom bolstered by his claim of social superiority told Hewes to mind his own business. When Hewes refused to withdraw, Maclom stuck Hewes in the head with his cane leaving a bloody gash and knocking Hewes unconscious. By now others had gathered at the scene, at which time Malcom ran back into his home.

Dr. Joseph Warren (Copley 1765)

With a throbbing head, Hewes went to see Dr. Joseph Warren, a physician and patriot leader. Dr. Warren told Hewes that he should report the attack and seek a warrant for Malcom’s arrest. Before Hewes could ever get a warrant, word had spread quickly about Malcom’s attack. An angry mob had gathered outside Malcom’s house on Cross Street. Malcom arrogantly baited the crowd through an upstairs window, claiming that the British Governor of Massachusetts would pay him twenty pounds sterling for every Yankee he killed. The mob grew violent and grabbed ladders to climb up to Malcom’s window. Men climbed the ladders, punched through glass windows, jumped into the house, took Malcom’s sword, and drug him out into the street. The mob grabbed a barrel of tar from a nearby wharf, heated it over a bonfire, and loaded Malcom into a cart. They took Malcom to the front of the Customs House and Old State House, the same place where the Boston Massacre had occurred four years earlier. In the bitter cold night the mob stripped off Malcom’s clothes and began to pour the scalding hot tar on his body. Once coated in hot sticky tar, they doused him with feathers.

Malcom was tarred and feathered near this point at the Old State House, also the site of the Boston Massacre

The mob then carted Malcom through the streets of Boston, eventually pulling him in front of Governor Hutchinson’s official residence and ordering Malcom to declare British Governor Hutchinson an enemy to his country. Malcom repeatedly refused. The mob grew even more enraged and took Malcom to the Liberty Tree, a huge Elm that grew near the center of the city. They tied a noose around Malcom’s neck and threatened to hang him if he continued to refuse to denounce the Royal Governor. The mob beat Malcom with sticks. By now Malcom was nearly unconscious. He finally relented stating that he would do or say whatever the mob wanted. The mob then carted Malcom through Boston’s streets back to his home near Copp’s Hill and dumped him out of the cart. Malcom was reportedly stiff as a log and nearly frozen to death. Amazingly, John Malcom survived. He was reportedly bed-ridden for eight weeks as his flesh peeled off from the tar.

Some patriots, including George Hewes, denounced the unruly mob that had nearly beaten Malcom to death. Others, like Samuel Adams, used the events as a propaganda tool to instigate further dissent against the British Government. In hindsight and by today’s standards the Boston mob’s violence against John Malcom seems horrible. To colonists living in Boston at the time, John Malcom embodied everything the patriots hated about the British. He was arrogant. He flaunted his higher social standing. He believed that the colonists could be beaten into submission. He thought the King could do no wrong.

It’s hard to say how much influence the boy sledding down Copp’s Hill had on starting a revolution. But it’s plain to see that the seeds of revolution grew in Boston on that cold winter’s night. History is full of the seemingly little things that grow into the movements of entire nations. A boy running his sled into John Malcom is one of them.

For more information about the Copp’s Hill Incident check out Nathaniel Philbrick’s book Bunker Hill: A City, A Siege, A Revolution.

So much of our past has present day applications. John and Abigail Adams wrote nearly 1,100 letters to each other over the course of their marriage. It’s a picture of a couple sharing their desires, flaws, problems, and pain. They were apart from each other for nearly a decade as John spent time in France, the Netherlands, and England, and yet they were happily married. So how did they do it?

John Adams was not perfect, far from it. He could be obstinate, self-centered, overly ambitious, and could wield a terrible temper. What made John different, was his ability to share his deepest thoughts, flaws and all, with Abigail and with his other close friends. John was a man not only connected with others, he was connected to his own heart. Adams’ wrote “I feel my own ignorance. I feel concern for knowledge. I have a strong desire for distinction.” Adams’ biographer, David McCullough, wrote, “But if self-absorbed and ambitious . . .the difference was that Adams wrote about it and was perfectly honest with himself.”

Adams shared this honesty through intimate communications with his close friends. McCullough describes Adams as having a “talent for close friendships.” Adams’ friend, Johnathan Sewall, wrote that John had “a heart formed for friendship, and susceptible to the finest feelings.” John described the following very personal feelings in a September 1, 1755 letter to his college friend, Nathan Webb: “At Colledge gay, gorgeous, prospects, danc’d before my Eyes, and Hope, sanguine Hope, invigorated my Body, and exhilerated my soul. But now hope has left me, my organ’s rust and my Faculty’s decay.”

Early on in his life Adams was keenly aware of the importance of close friends as seen in his eloquent and powerful statement in a letter to Webb dated October 12, 1755:

“Friendship, I take it, is one of the distinguishing Glorys of man. And the Creature that is insensible of its Charms, tho he may wear the shape, of Man, is unworthy of the Character. In this, perhaps, we bear a nearer resemblance of unbodied intelligences than any thing else. From this I expect to receive the Cheif happiness of my future life, and am sorry that fortune has thrown me at such a distance from those of my Friends who have the highest place in my affections. But thus it is; and I must submit. But I hope e’er long to return and live in that happy familiarity, that has from earliest infancy subsisted between yourself, and affectionate Friend, John Adams”

Adams carried this affinity for close connected friendship into his marriage with Abigail. The two were married on October 25, 1764. Over the course of their marriage, John continued to share his deepest feelings with his wife through his letters, although John readily acknowledged that Abigail was the better writer. Both John and Abigail recorded that they found it easier to share intimate feelings in their letters rather than in conversation. There are hundreds of examples of the two sharing their feelings in their letters, but the following exchange is just one example. In late 1775, Abigail’s mother Elizabeth Quincy Smith died. Abigail put her feelings in an October 9, 1775 letter to John .

“But the heavy stroke which most of all distresses me is my dear Mother. I cannot overcome my too selfish sorrow, all her tenderness towards me, her care and anxiety for my welfare at all times, her watchfulness over my infant years, her advice and instruction in maturer age; all, all indear her memory to me, and highten my sorrow for her loss. At the same time I know a patient submission is my duty. I will strive to obtain it! But the lenient hand of time alone can blunt the keen Edg of Sorrow. He who deignd to weep over a departed Friend, will surely forgive a sorrow which at all times desires to be bounded and restrained, by a firm Belief that a Being of infinite wisdom and unbounded Goodness, will carve out my portion in tender mercy towards me! Yea tho he slay me I will trust in him said holy Job….Still I have many blessing[s] left, many comforts to be thankfull for, and rejoice in. I am not left to mourn as one without hope.”

Abigail’s October 9, 1775 letter to John

John, who was in Philadelphia attending the First Continental Congress, responded, “Really it is very painfull to be 400 Miles from ones Family and Friends when We know they are in Affliction. It seems as if It would be a Joy to me to fly home, even to share with you your Burdens and Misfortunes. Surely, if I were with you, it would be my Study to allay your Griefs, to mitigate your Pains and to divert your melancholly Thoughts.When I shall come home I know not. We have so much to do, and it is so difficult to do it right, that We must learn Patience. Upon my Word I think, if ever I were to come here again, I must bring you with me.”

John’s October 19, 1775 letter to Abigail

This exchange between John and Abigail is just a taste of the deep thoughts and emotions the couple were able to share with one another. Historian, Joseph Ellis in his book First Family Abigail and John Adams, writes that John and Abigail’s letters “constitute a treasure trove of unexpected intimacy and candor, more revealing than any other correspondence between a prominent American husband and wife in American history.” Ellis summarizes the uniqueness of this type of intimacy as follows:

“The distinctive quality of their correspondence, apart from its sheer volume and the dramatic character of the history that was happening around them, is its unwavering emotional honesty. All of us who have fallen in love, tried to raise children, suffered extended bouts of doubt about the integrity of our ambitions, watched our once youthful bodies betray us, harbored illusions about our impregnable principles, and done all this with a partner travelling the same trail know what unconditional commitment means, and why, especially today, it is the exception rather than the rule.”

So how did John and Abigail do it: Through intimate communication. Today more then ever, and especially with guys, we’ve lost the ability to share our inmost feelings and desires, partly because we don’t really even know what those feelings are. Text messaging our wives about what’s for dinner or who’s picking up which kid is as about as intimate as most marital communications get now days. Somewhere along the way guys have lost the ability to know themselves, faults and all, and openly share their fears, joy, loves, wounds, and inadequacies with a spouse or close friend. John Adams got it when he said that deep friendship is one of the distinguishing Glorys of man. Without it we aren’t really men. Although he lived 200 hundred years ago, John’s message is needed today more than ever.

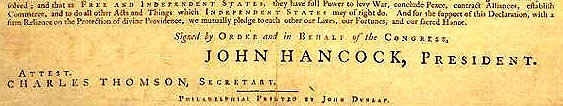

It’s hard to think of the symbol of the United States without picturing a majestic bald eagle swooping through the air. Charles Thomson’s Great Seal of the United States, which pictures the bald eagle, was designed and accepted by Congress in 1782. Thomson is a little known founding father, with his name appearing next to John Hancock’s on the Declaration of Independence. He served as the Secretary of the Continental Congress for fifteen years and was held in high regard by his peers for both his intelligence and honesty.

In John Trumbull’s painting of the signing of the Declaration of Independence, Charles Thomson is pictured standing to the right of John Hancock sitting in the chair

Charles Thomson’s name on the Declaration of Independence

Picking a design for the Great Seal was not easy. Starting back in 1776, Ben Franklin, Thomas Jefferson, and John Adams debated how best to design a national symbol. The three men had varying ideas ranging from Adams wanting Hercules to Franklin wanting Moses and Pharaoh. A couple of artists were hired to come up with designs. Both threw out these founding father’s ideas and came up with designs featuring a Goddess of Liberty. Congress rejected all of these ideas and in 1782 turned to another committee to design the seal. This committee came up with a complicated design featuring an eagle and a dove, which Congress also rejected. Desperate for an idea, Congress turned to Thomson for help. Thomson wrote his description of the seal featuring the American Bald Eagle. Thomson’s design was approved by Congress and the bald eagle became a national symbol.

Where then does the turkey come in to play in all of this? Contrary to what many think, Benjamin Franklin never seriously proposed that the turkey be used as our national symbol. The idea that Franklin wanted the turkey to be our national bird comes from a letter he wrote to his daughter Sarah (Sally) Franklin Bache in 1784 while Franklin was still in France. Sally was born to Ben and his wife Deborah on September 11, 1743. Sally was actively involved in politics, especially for a woman during this period. We know much about Sally through her personal letters between herself and her father.

Sally Franklin Bache

In his letter to Sally, Franklin comments that the eagle pictured in the newly adopted seal looks like a turkey. In true Franklin form, he goes on to compare the differences between the bald eagle and the turkey from a moral perspective and clearly favors the turkey over the eagle. Franklin claims that the bald eagle is a bird of bad moral character as it steals fish caught by other birds and is a coward by letting littler birds fly around him and drive him away from their nests. Franklin goes on to claim that he wished the Great Seal really did picture a turkey instead of a bald eagle. Franklin notes that while the bald eagle is found in various nations, the turkey is truly native to American soil. According to Franklin, turkeys are courageous birds that would “not hesitate to attack a Grenadier of the British Guards who should presume to invade his Farm Yard with a red Coat on.” Last but certainly not least, Franklin makes note that turkeys are a delicacy fit for a feast of kings. By comparison, you don’t see many eagles roasted to perfection with the dressing and sides prepared for a feast. Thus, although the turkey may have never been truly considered a candidate for our national symbol, I’m with Franklin. The turkey beats the bald eagle, especially on Thanksgiving.

The British Grenadiers were an elite 18th century fighting force. These soldiers were called upon to be in the front lines of an attack and would lob primitive grenades onto the enemy before attempting to storm whatever walls and other battlefield obstructions lay in their path. Grenadiers were usually handpicked for their stature and strength and then given tall hats to make them appear even more intimidating to the enemy. The hats had small brims so as not to impede throwing and were often decorated with embroidery or fur.

Grenadier’s carried their grenades in a leather pouch slung over the shoulder, usually on their right side. The grenades were just iron balls filled with gun powder with a fuse on top. The fuse would be lit and then the iron ball would quickly be thrown, or sometimes rolled, into a line of enemy troops. The idea of standing in the line of fire to light a fuse on an iron ball that will explode in your hand if not thrown quickly is, to say the least, a bit terrifying. Thus, Grenadiers were considered some of the bravest hearts in the British army.

A British Grenadier’s Grenade

Grenadiers needed a way to light their grenades, and butane lighters hadn’t yet been invented. The answer was a piece of slow match, or match cord, that was carried in a match case attached to the breast of the Grenadier’s uniform. Slow match was made by soaking rope in a nitrate solution. Interestingly, and a little gross, the nitrates were often extracted from urine or manure. After soaking, the rope was allowed to dry. Infused with the potassium or sodium nitrate, the rope would burn steady and very slowly, allowing a Grenadier to light the fuse on his grenade in the midst of battle.

A British Grenadier’s Match Case

While Grenadiers were still considered an elite fighting force at the time of the American Revolution, their use of grenades had dwindled somewhat. Military tactics had changed and the wilderness of the American Colonies did not lend itself to grenade use. Nevertheless, British Grenadiers were feared by American soldiers. Their tenacity and bravery were known to send untrained American soldiers running. At the Battle of Brandywine on September 11, 1777, British Grenadiers broke the American line of battle and chased the American soldiers for nearly two miles, all in the face of heavy cannon fire. Known for their many acts of bravery on the battlefield over the course of British military history, the Grenadiers have been given their own battle march. Here’s a few lines from the song and a link to the familiar tune.

When e’er we are commanded to storm the palisades, Our leaders march with fuses, and we with hand grenades; We throw them from the glacis about the enemies’ ears, Sing tow, row row row , row row row, For the British Grenadiers.

And when the siege is over, we to the town repair. The townsmen cry ‘Hurrah, boys, here comes a Grenadier’. Here come the Grenadiers, my boys, who know no doubts or fears. Sing tow, row row row , row row row, For the British Grenadiers.

The fighting prowess of these Grenadiers, professionally trained warriors, makes me marvel all the more at how we won the war for independence. It’s truly a testament to the resiliency of the American Colonists who were able face this formidable enemy. Huzzah!

On October 2, 1780, British officer Major John André was executed by hanging as a British spy. While many pleaded that André be spared, including American officers such as Alexander Hamilton, George Washington chose to carry out the execution. André had been discovered out of uniform, behind enemy lines, and carrying the confidential papers Benedict Arnold had given him as the two men conspired to turn the American fort at West Point over to the British. However, André was not just any spy, he was the Adjutant-General to the British Army. He was also a handsome, youthful, thirty-year-old, with charm and grace that many American officers admired. After a Board of American officers found André guilty as a spy, Washington would not be persuaded to spare his life.

Major John Andre

In 18th century warfare, most captured officers were treated well and then exchanged for enemy officers also captured by the opposing side. André, however, was a spy. To Washington, had André succeeded in his task of carrying the plans for West Point into enemy hands the war would have likely ended in American defeat. Such treachery had to be punished by death.

Proponents of André looked to the series of unfortunate events that led to André’s capture in civilian clothes, and blamed Benedict Arnold as the treacherous traitor that caused André’s demise. It is true that Arnold gave very little thought to the safety of his British counterpart in his plan to turn traitor. André had been dressed in his British uniform when he first met with Arnold on September 20, 1780. André had sailed up the Hudson River in the British vessel, Vulture, and been secretly rowed ashore for a clandestine meeting with Arnold. The next morning the Vulture came under fire from American forces and had to sail back down the Hudson. While it still would have been possible to get André back aboard the Vulture the following night, Arnold convinced André to change into civilian clothes and ride south through American held ground in New York to return to the British.

Arnold giving Andre the plans to West Point

Arnold gave André a signed pass, in case he was questioned. Arnold’s aide Joshua Smith accompanied André on horseback all the way back to within a mile of the enemy line. He then left André. As André was just about back to British held territory, he was stopped by three men. One of the men was wearing a Hessian overcoat and André assumed the men were British Tories. André asked the men which side they were on. They lied claiming they were with the British. André then admitted that he was a British officer on urgent business. The men searched André and found the secret papers tucked in his stockings.Thus began not only André’s undoing but that of Benedict Arnold as well.

When André realized that his life would not be spared, he wrote a letter to Washington asking that at the very least he be executed with honor by a firing squad and not the dishonorable death by hanging. Once again, Washington held firm. André was to be hanged. Further endearing himself to the hearts of officers from both sides, Andre faced his death with unwavering bravery. He walked to the gallows unbound, with two men holding either arm. He climbed up into the ox cart under the gallows. He put a handkerchief over his eyes. While the executioner was there ready to put the noose around his neck, André took it from him and put it on himself. André reportedly stated,”I pray you to bear me witness that I meet my fate as a brave man.” The cart pulled away and the deed was done.

While Washington took considerable grief for carrying through with André’s execution, he knew that this was not a time for compromise or to appear weak. The fate of a nation was resting in the balance and a message had to be sent to everyone that spies would be hanged. For John André his fate was fixed to the traitor Benedict Arnold who escaped into British hands, leaving Andre to die. In that respect, André’s death truly is unfortunate.

For a great account of Andre’s capture and execution, check out Nathaniel Philbrick’s, Valiant Ambition: George Washington, Benedict Arnold, and the Fate of the American Revolution

September 19, 1777 marks the opening battle at Freeman’s Farm that ultimately led to the decisive American victory a few weeks later, known as the Battle of Saratoga. The British lost at Saratoga primarily due to the vanity, pride, and self-absorption of British Generals Howe and Burgoyne. American Generals Benedict Arnold and Horatio Gates were not far behind their British counterparts when it comes to putting self-interest over the good of the cause. In short, all involved forgot that there is no “I” in “TEAM”.

John Burgoyne – portrait by Joshua Reynolds 1766

John Burgoyne was a British general known for his vanity, earning the name Gentleman Johnny. In 1737, at the age of fifteen John entered the army by buying an officer’s commission as a sub-brigadier in the Third Troop of Horse Guards. A notorious gambler, Burgoyne had to sell his officer’s commission in 1741 presumably to pay gambling debts. A few years later, Burgoyne reenlisted as a cornet in the First Royal Dragoons (British cavalry) and saw action in the War of Austria Succession. He was promoted to lieutenant and then in 1747 somehow came up with 2,000 pounds (probably more gambling) to buy a commission as a captain with the Royal Dragoons. Notably charming and handsome, John won the affection of his best friend’s sister Charlotte Strange, daughter of Lord Derby. Lord Derby would not approve the marriage given Burgoyne’s lower class status, but the two eloped spending time in France. Lord Derby eventually warmed to Burgoyne as his son-in-law and helped in John’s quick rise in the British army. After winning military glory in Portugal, Burgoyne returned to England and was seated in the British Parliament in 1762. Not only a Parliamentarian, Burgoyne also became a playwright. Indicative of his character, Burgoyne was known for his boastful statements. Upon arriving in Boston in 1775, now a major general, Burgoyne reportedly stated: “Ten thousand peasants keep five thousand king’s troops shut up! Well, let us get in and we’ll soon find elbow-room.”

General Sir William Howe

British General William Howe started his military service as a cornet with the Duke of Cumberland’s Dragoons in 1746. Howe was of noble birth as son of Viscount Emanuel and had close ties to royalty which helped advance his military career. During the French and Indian War, Howe was recognized for his ability to lead men in battle and was promoted to General. Howe then became leader of British troops in the American Revolution. Howe successfully captured New York in 1776, but was unable to land a decisive victory against the American army and end the war.

It is well-known that Howe did not like Burgoyne, considering him to be a grandstander of low birth. When plans were made for Burgoyne to march south from Canada down the Hudson Valley, with Howe moving north from New York, Howe wanted no part in seeing Burgoyne obtain military acclaim through a successful campaign. Howe wanted his own success and so instead of marching to meet Burgoyne’s army, Howe headed south to Philadelphia where he intended to capture the rebel capital. Burgoyne, confident that Howe would join him from the south, continued his march into the wild interior of New York. Howe of course never came. Burgoyne’s army was no match for the wily wilderness fighters that made up the Northern American army. Daniel Morgan and his expert riflemen relentlessly picked off British officers throughout the fighting at Freeman’s Ford with British losses totaling 600 hundred men. Instead of retreating back to Fort Ticonderoga, Burgoyne, always the gambler, continued to attempt to break through the American lines. Burgoyne eventually surrendered his entire army on October 17, 1777.

American General Horatio Gates

The northern division of the American army was also plagued with leaders bent on self-advancement. With Washington trying to keep Howe from taking Philadelphia in the south, General Horatio Gates was in command of the northern army. A disgruntled Benedict Arnold served alongside Gates. Congress had recently passed over Arnold for promotion despite his efforts in Quebec and Ridgefield, Connecticut. As Burgoyne advanced into New York, Arnold wanted to fight and Gates did not. Over the course of the Saratoga battles, Gates and Arnold fought incessantly among themselves. Eventually Gates removed Arnold from field command. Throughout Saratoga, Gates never left the safety of his headquarters. Arnold could no longer stand Gates’ inaction and on October 7, 1777 rode out of camp onto the battlefield in what has been described as a drunken rage. Arnold was later wounded in an attack on a British redoubt. While Arnold recovered from a shattered femur, Gates took the credit for the victory at Saratoga and would use it as a tool to attempt to unseat Washington as Commander-in-Chief. Snubbed once again, Arnold began down his path of treason.

Trumbull’s painting of Burgoyne surrendering to Gates. Benedict Arnold is notably missing from the painting.

Saratoga has been touted as the turning point in the war. The Americans captured an entire division of British soldiers. The victory also helped secure French naval support. While Saratoga was an important American victory it is also a reminder of what can happen when self-promotion becomes the ultimate goal. Had Howe marched north instead of selfishly heading to Philadelphia, the course of history may have been forever changed. Had Gates allowed Arnold to fight, and shared credit for the victory, Arnold may not have committed treason. While it’s not uncommon for military leaders to seek glory and promotion through actions on the battlefield, Saratoga is an example of egos on steroids. It displays some of humanity’s worst character qualities and serves as a lesson for us all.

For more on the stories of Saratoga check out: The Generals of Saratoga: John Burgoyne and Horatio Gates by Max M. Mintz and William Howe and the American Revolution, by David Smith.